Gold Carry Trade

What paying the "cost of carry" means for gold traders...

INVESTORS BUYING exchange-traded commodity funds have been dealing with the vexation of contango for months, writes Brad Zigler for Hard Assets Investor.

You know about contango, right? It's when you can get your oil, your gold or any other storable commodity delivered today for a lower price than you'd pay for waiting a month or more.

Put another way, contango makes buying a commodity for future delivery more expensive. But why should waiting cost more? After all, in retail transactions across the economy, buyers typically pay a premium for express, rather than delayed shipment.

But the futures markets are a different kettle of fish (or oil, or gold). Once you've contracted to take possession of the commodity – as you do in a futures contract – you pick up the "carrying costs" until its actual delivery. These costs include financing, storage and insurance charges.

Gold & the Cost of Carry

If you're paying these costs of carry, as they're known, it stands to reason that there must be a commodity to carry. And so the carrying cost signifies a commodity in adequate or more-than-adequate supply. There's plenty of the stuff to go round, and so the storage and insurance costs (in the case of gold, for instance) are therefore a burden. Holding the commodity right now is not a particular privilege.

If you leave the other party in charge of paying those costs for the next month (or more), then you'll have to pay for the inconvenience they're put to.

An opposite condition – the inverted market, also known as "backwardation" – is marked by progressively lower prices for future delivery. That's because there's a relative lack of the commodity to satisfy demand right now. In such a market, nobody is willing to wait for delivery and so the "front month" contract (if not the Spot Price for immediate settlement) is bid higher.

Many commodities flip-flop between normality (contango) and inversion (backwardation) as supply and demand forces interact across the annual seasons and broader economic cycle. Crude oil, for example, moves between contango and backwardation as demand pulsates with the rhythm of economic expansion and contraction, and as producing countries throttle production to maintain pricing power or encourage demand.

Gold's Contango: Small But Constant

There's one commodity, however, that's in constant contango: Gold Bullion.

Gold's resistance to backwardation rests upon its utility. Because gold isn't, for the most part, consumed. Virtually all of the gold that's ever been mined and refined is still with us; it gets recycled, not destroyed.

You can't say that about oil or wheat. Oil becomes greenhouse gas and wheat becomes, well ultimately, fertilizer.

Put rather crudely, the supply of gold keeps rising as new metal is mined. Now, it may take different forms over time – bullion, jewelry or Gold Coins – but it's still gold. There are times, however, when deliverable gold may be in short supply. Often, this comes about because of the carry trade that's developed for the metal.

Central banks, which previously held gold as a sterile reserve, now actively lease metal to produce income. Lending gold to other financial institutions, to producers and to fabricators, produces a modest return for the central bank. Lease rates are traditionally pegged below those of other borrowings such as the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR).

The difference between LIBOR and the gold lease rate, in fact, determines gold's contango. Variation in gold's contango, not surprisingly, is influenced by changes in credit market conditions more than by any other factor. Aggressive central bank rate cuts, for example, will narrow the contango, while a hawkish inflation stance will generally engender wider premiums.

In a lease deal, a gold mining producer – or perhaps a jeweler or a trader – borrows metal. He then sells it in an open market transaction, investing the proceeds, perhaps into an income-yielding asset such as Treasury securities or gilts, and pocketing the gap between the lease rate and his investment yield.

When the lease contract is closed, bullion is either bought through an open market purchase or, for a commercial producer, delivered from mine output.

Operationally, a lease transaction is the equivalent of a futures short sale and thus can be used for investment or hedging purposes. The transaction makes money for the borrower so long as the Spot Gold Price trades below the forward value implied by the contango.

Rising Gold Prices may force borrowers to close their contracts and, as a result, shorten the supply of deliverable metal. Producers hedged with lease contracts, for example, may accelerate deliveries against them and, as well, refrain from transacting new leases. Gold which would otherwise be destined for the open market then ends up going to the central bank.

Gold Carry Trade Offered Easy Money to Miners

Lately, gold-mining producers – particularly publicly traded miners – have lightened or even closed their hedge books in response to shareholder ire over poor share price performance during gold's recent ascent.

Even with producers out of the lease market, spot gold supplies may still be reduced as fabricators and speculative traders close their contracts to cut their losses, too.

The impact on possible Gold Prices? Leasing takes place in a wholesale market where transactions are measured in thousands, if not millions, of ounces. Smaller traders are left to exploit gold's monetary utility in the futures markets where deals are denominated in hundreds of ounces.

As an example, let's say it's April, and spot Gold Futures are offered at $956.20 an ounce. Let's also say June futures are bid at $958.50. Buying April gold and selling June would earn you a premium of $2.30 – or 0.24% – over the spot price. Adjusted for storage costs, the annualized premium commanded by June futures is 0.78%, which represents a 58 basis point (0.58%) yield pickup over the three-month Treasury bill rate, then at 0.20%.

If you buy and take delivery of April gold while simultaneously selling a countervailing position in June futures, you could capture the excess return offered by the futures curve. You'd be insulated from price risk during your holding period, since you'd own the gold to be delivered in June, but at the same time you'd need to have the means to take possession of spot metal and make delivery at the other end. That means contracting for storage and bearing the costs. Which is a hassle that explains the 58 basis points premium over the risk-free rate.

(Note that the spread over a commercial interest rate, such as LIBOR, would be a lot less; in our example, the pickup would be only 26 basis points.)

As long as a trader can keep transaction and storage costs below the premium, there's money to be made in the spread. And as you can see, the gold carry trade is pretty straightforward. Vaults abound to provide secure storage for precious metal. But that's not the case for other commodities, though. Take oil for example.

Bulk petroleum storage facilities are necessarily large and scarce. They also present security and environmental consequences, which raises insurance charges. The per-unit cost of storing oil is a lot higher than gold's, so there have to be much fatter premiums offered to justify cash-and-carry operations.

Back in mid-January, for example, crude's quarterly net carry got as wide as $14 a barrel, a mighty big incentive to stash oil away for future sale when you consider the current carry's averaging less than $2.

The Tale's In The Spread

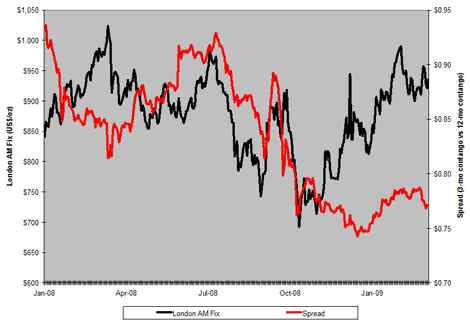

Gold's forward curve is also a sort of telegraph of market conditions and is monitored by savvy investors to gauge their trading prospects. Take, for example, circumstances since early 2008.

As LIBOR rates fell, so too did the spread between 3-month and 12-month forward contracts. The basis ultimately narrowed to 81 cents an ounce when the bull market reached a crescendo on March 17.

Then bull spreads – buying nearby contracts but also selling longer-dated futures – would have been ideal trades to capitalize upon the decline in money market rates. (What are known as "Bear spreads", going long of forward contracts and short of nearbys, are favored when the opposite condition, i.e. higher interest rates, are expected...)

Of course, with interest rates being kept as low as they are now, gold traders are left wondering just how much room remains for bull spreads.

Email us

Email us